Housing affordability (or the lack thereof), as well as public housing, were major issues in the last presidential election. Vice President Kamala Harris planned to build three million new housing units while effectively punishing corporations with large portfolios of single-family homes through various policy proposals.

Some activists want to go even further. For example, a group named People’s Action wants to “decommodify” housing—or, in other words, make all housing in the United States government housing.

President Trump, for his part, ran on reducing grocery prices or inflation in general. Housing isn’t directly measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), but it still factors greatly in the cost of living. In Trump’s first term, he sought to cut the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s (HUD) budget, but was blocked by Congress.

It would not be surprising if Trump again tried to cut HUD’s budget despite public housing being long thought of as the third rail in politics. Indeed, it has a long history in the United States and the world over. And while the reasons behind public housing have been completely understandable, its results have often failed to live up to the promise.

Public Housing’s Earliest Beginnings

Examples (or quasi-examples) of public housing—i.e., housing provided by a governing authority to people subject to that government—have existed in one form or another since the dawn of civilization. That said, what we think of as the government or state doesn’t exactly translate to ancient or medieval civilizations.

Semantics aside, public housing still goes back a long way. For example, Deir el-Medina was a village of craftsmen and artists that built the tombs in the Valley of the Kings between the 18th and 20th Dynasties of the New Kingdom of Egypt (between approximately 1550 and 1080 BCE).

In ancient Rome, ordinary Roman citizens often lived in a kind of apartment building called an insula. These often shoddily constructed buildings were, unfortunately, quite susceptible to fire and, given their proximity to each other, made disasters like the Great Fire of Rome more likely to happen. The insula was a sort of pseudo-public housing, as they tended to be owned by wealthy Roman patricians, many of whom were senators who controlled Rome’s government.

And, of course, throughout history, there have been slave quarters, which, in a very exploitative way, could be seen as an extremely unpleasant form of public housing.

As we move from ancient times into the Middle Ages, concepts of property—at least in Europe—looked far different than they do today. Feudalism amounted to a series of pledges and obligations between lords and their vassals, with the king being at the top of the ladder.

At the bottom were the serfs, who worked their lord’s lands for a percentage of their produce. And since they were bound to that land and prohibited from leaving, their housing resembles public housing provided by the government (or the lord, in this case) more so than in a market economy.

The Modern History of Public Housing

Gradually, public housing became less of a governing authority (be it a government, plutocrat, slave owner, or feudal lord) providing housing to his subjects, but instead, a way for governments to provide housing at a reduced cost to those who could not easily afford it.

One of the first examples of this was the Fuggerei. According to the Fugger Foundation, “The Fuggerei is the oldest existing social housing complex in the world, a city within a city with 67 buildings and 142 residences, as well as a church.”

These houses were constructed by Jakob Fugger in 1521 for 150 needy Catholic citizens of Augsburg at a substantially reduced rate. Jakob Fugger was the head of the extremely wealthy Fugger family (some estimated Jakob’s wealth amounted to 2% of all of Europe’s wealth at the time) and a major supporter of the Habsburgs, who ruled the Holy Roman Empire at the time.

Of course, this was during the Reformation, and the Fuggers were trying to lure support away from the Protestant reformers. (Just four years earlier, Martin Luther had posted his famous 95 Theses to the door of the Wittenberg Castle church.) The previous family to hold the title of being the richest in Europe—the Medicis of Florence, Italy—had instead bestowed their charity not on the working poor but on the arts instead.

This is particularly true of Lorenzo De Medici, who was the banker to the Pope, de facto ruler of Florence, and patron to Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and many others. The Italian Renaissance, in no small part, was made possible by the Medicis. (This is also true of a variety of wars, such as the War of the Roses in Europe, in which they financed both sides.)

While the social housing provided by various rules and oligarchs in the early modern era was illustrative of things to come, it still amounted to rich individuals performing charitable works. Public housing, as we know it today, really began to take off at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution.

The Industrial Revolution, Urban Crowding, and Demands for Public Housing

The Industrial Revolution first began in Britain sometime between 1760 and 1780 before migrating to the rest of Europe and then throughout the world. A variety of factors made this possible, including new technologies like the steam engine and spinning ginny, the enclosure acts that moved many rural peasants off their land into the cities, and large coal deposits near those cities to act as fuel for Britain’s burgeoning industrialization.

You might also like

However, as the cities grew rapidly, urban blight, disease, overcrowding, and the like went right along with it. Despite unparalleled growth in history, the urban poor were doing quite badly. For example, between 1850 and 1870, the world output of coal increased by 250% and iron by 400%, while the amount of railroad mileage laid went from 2,808 miles in 1840 to 52,922 in 1870, to its peak of 254,037 in 1916.

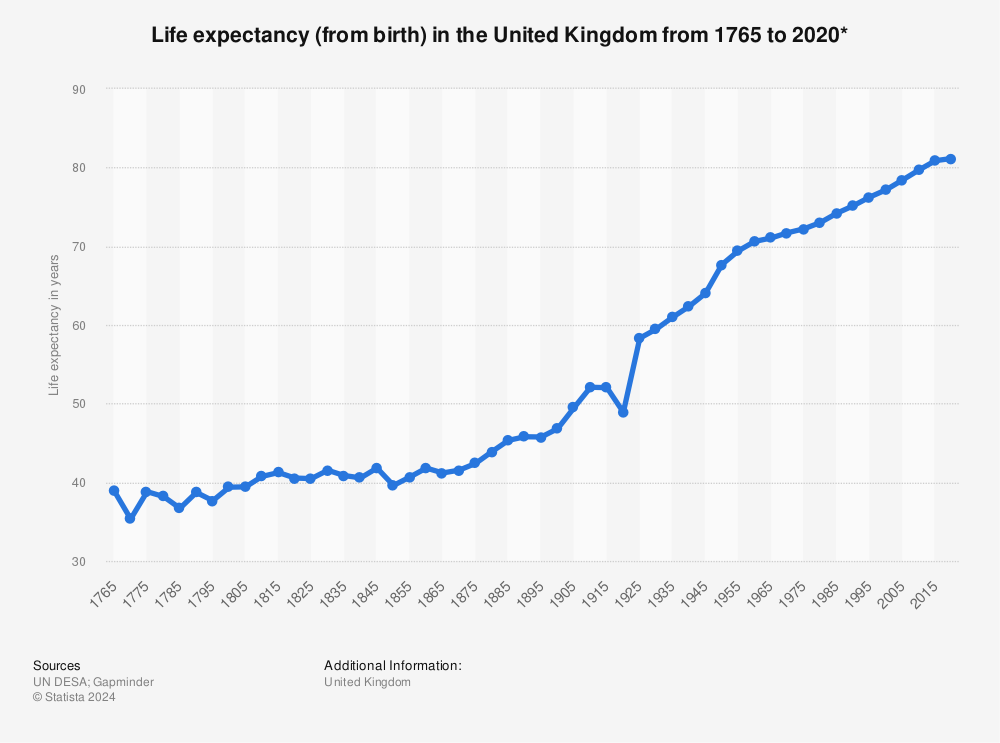

On the other hand, the average height of British citizens actually declined in the first half of the 19th century due to poor nutrition and living conditions. Indeed, life expectancy in Britain actually flatlined and even fell slightly at the beginning of the 19th century before finally starting to rise again in the second half of the century.

Find more statistics at Statista

Thus, it’s not surprising that there would be a reaction. This came in moderate forms like the Chartist movement in Britain and radical forms like Frederich Engels, who wrote his blistering critique of the early capitalist system, The Condition of the Working Class in England, and Karl Marx, who wrote The Communist Manifesto in 1848, the same year as a continent-wide revolt took place.

The response of the British authorities to these challenges was modest. This mostly consisted of shipping off much of its poor and riffraff to the New World and putting in a few regulations on working conditions, including limiting working hours, factory inspectors, and regulations regarding women and children.

However, virtually nothing was done about housing until the Housing and Working Classes Act of 1885, which put in some basic regulations and allowed the authorities to clear slum housing. Other than that (and private charity, of course), the main government form of public housing was the workhouses for orphans, the poor, and the intransigent that were so thoroughly pilloried by the likes of Charles Dickens.

While the condition of the working class was quite poor at the time, Marx’s and Engels’ theories never made much sense. By the time the first volume of Karl Marx’s magnum opus, Das Kapital, was published in 1867, the condition of the working class had already been improving substantially, whereas he predicted they would become poorer and poorer until the inevitable revolution. The working class was supposed to be ground into dust, but arguing today that working people are worse off than they were in the early 19th century is beyond ridiculous.

Indeed, pretty much all of Marx’s theories failed. He predicted the revolution would come in the most advanced capitalist states like Britain, the United States, or Germany. Instead, it happened in pseudo-feudalist states as they were industrializing, like Russia and China.

Marx also didn’t publish the second and third volumes of Das Kapital during his lifetime (Engels put them together and published them in 1885 and 1894, respectively). This was probably in large part because Marx’s theory was that capitalists stole the “surplus value” from laborers. But if that were so, then why did labor-intensive industries not have a higher profit margin than capital-intensive industries?

Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk counted no less than four different and rather contradictory explanations for this inconsistency (Karl Marx and the Close of His System, pg. 32). It seems the one Marx settled on the most is that the capitalists broke down old feudal barriers, which allowed competition to smooth out the difference in profit levels between industries despite labor being exploited more in some industries than others. This, of course, is unfalsifiable and akin to saying “just trust me, bro.”

And, of course, the whole idea behind the labor theory of value is absurd to begin with. Marx only includes “socially necessary labor” but doesn’t acknowledge that some labor is more valuable than others, except for noting that a certain amount of unskilled labor adds up to skilled labor. This is false, as 10 unskilled laborers or even 100 cannot do what one, say, electrician can.

Further, Marx implies that anything not mixed with labor is of no value when, obviously, that is not true. A gold deposit has value, even if it’s just sitting there. And of course, he ignored the skill and effort required in entrepreneurship, business management, etc. and just assumed it to be theft.

Still, Marx did inspire the revolutions that took place throughout the early-to-mid-20th century. With them, all housing became effectively universally government housing.

And oh boy, did they create some of the ugliest, soul-crushing, cookie-cutter block housing the world has ever seen. The Soviet version were known as Khrushchevkas. Here’s one example of such an abomination:

Sometimes the cure is worse than the disease, a theme we will return to shortly.

Public Housing in the United States

As noted, what exactly is and isn’t public housing is a bit trickier to define in early periods. The company towns that popped up throughout the Midwest in the 19th century were effectively corporate-owned cities with public housing for their workforce (and their own currency, for that matter, called scrip, to use in company-owned stores). Indeed, we see the same thing to a certain extent with some of the enormous corporate campuses like Apple Park.

What began the push for public housing was the rapid urbanization brought on by the nation’s growing industrialization and large-scale immigration of the late 19th century. Jacob Riis became famous for his book How the Other Half Lives and photos of overcrowded, squalid housing.

While this created the impetus for public housing, the policy didn’t follow suit in any notable way until the Great Depression and Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. The Public Works Administration subsidized a variety of construction projects, including housing.

Then came the National Housing Act of 1937, which provided subsidies to local public housing agencies. This was partially inspired by Catherine Bauer’s influential Modern Housing, which advocated for housing to be seen as a public utility. The spirit of that economically depressed age moved away from the free market and toward government intervention.

After World War II, public housing kicked into high gear throughout the Western world. In Europe, much of this had to do with rebuilding after the war’s devastation. In the United States, there was a housing shortage as vets returned from the war, and the so-called baby boom began.

Harry Truman passed the Housing Act of 1949, which is when the large and infamous public housing projects began. It also pushed for slum clearing and urban renewal. Not surprisingly, this policy did quite a poor job of it, as they ended up destroying substantially more housing than they built and upended numerous vibrant local communities along the way.

It was in this period that the United States saw the construction of some of the largest (and most disastrous) public housing projects in history. This included Cabrini-Green Homes in Chicago (housed 15,000 people, constructed between 1942 and 1962, demolished in 2011); the Robert Taylor Homes also in Chicago (housed 27,000 people, constructed in 1961, and demolished in 2007); and Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis (housed 10,000 people, constructed in 1951, and demolished in 1976).

These public housing projects became infamous and simply referred to as “the projects.” As Howard Husock explained in his book America’s Trillion-Dollar Housing Mistake, these housing projects concentrated the poorest people in one place that “radiate dysfunction and social problems outward, damaging local businesses and neighborhood property values. They hurt cities by inhibiting or even preventing these run-down areas from coming back to life by attracting higher-income homesteaders and new business investment.” This is not at all what was originally intended.

“Public housing spawns neighborhood social problems because it concentrates together welfare-dependent, single-parent families, whose fatherless children disproportionately turn out to be school dropouts, drug users, nonworkers, and criminals. These are not, of course, the families that public housing originally aimed to serve. But as the U.S. economy boomed after World War II, the lower-middle-class working families for whom the projects had been built discovered that they could afford privately built homes in America’s burgeoning suburbs, and by the 1960s, they had completely abandoned public housing. Left behind were the poorest, most disorganized nonworking families, almost all of them headed by single women. Public housing then became a key component of the vast welfare-support network that gave young women their own income and apartment if they gave birth to illegitimate kids. As the fatherless children of these women grew up and went astray, many projects became lawless places, with gunfire a nightly occurrence and murder commonplace.” (America’s Trillion-Dollar Housing Mistake, pp. 30-31)

Cabrini-Green became so dangerous that the police refused to even enter the building. Residents complained of living in the same type of squalor Jacob Riis described but also in constant fear for their lives. In 1992, a 7-year-old boy was shot and killed next to Cabrini-Green while walking to school. Cabrini-Green became the poster child for dysfunctional public housing and was thankfully demolished in phases between 1995 and 2011.

Since then, public housing has moved toward a more dispersed method of providing subsidies for those with low income that doesn’t concentrate poverty in one place, making it all the harder for those stuck in such situations to get out.

In 1974, HUD began the Section 8 Housing Choice Voucher Program, which allows voucher holders to have their rent subsidized by the government in privately owned units whose owners accept vouchers. (Although, whether a landlord has the right to accept or reject Section 8 vouchers is being eroded. Today, 17 states, 21 counties, and 85 cities ban so-called “source of income discrimination” and require landlords to rent to those on Section 8.)

The government also provides tax credits to developers to build Section 42 or LIHTC (Low Income Housing Tax Credit) properties that require landlords to charge below-market rent to low-income tenants in exchange for tax credits.

These programs are far from perfect. Section 8 is a cumbersome process with all sorts of bureaucratic delays and costs. For Section 42 projects, the costs of developing them are notably higher than market-rate properties, mostly because of the “soft costs” (i.e., attorneys, permitting, etc.).

Still, these programs are a great improvement over the large public housing projects that preceded them. As a study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland notes, “…closing large public housing developments and dispersing former residents throughout a wider portion of the city was associated with net reductions in violent crime, at the city level.” The quality of Section 8 and Section 42 housing is also far superior to that of the old, dilapidated housing projects like Cabrini-Green and Pruitt-Igoe.

Final Thoughts

Indeed, the history of public housing has clearly demonstrated that while the needs are real, the results are often far from ideal. The market is still the best place to provide at least the majority of housing. And while there is a place for government-subsidized or even government-built housing, policies regarding such housing need to be enacted very carefully. After all, history is replete with examples of the cure being worse than the disease, and we all know where paths paved with good intentions can lead.

Few things offer better examples of that than the history of public housing, particularly in the United States.